Open Ocean: the Blue Desert

Silky Shark

As our search for food and recreation pushes us ever farther into offshore waters, we are encountering Silky Sharks (Carcharhinus falciformis) with greater and greater frequency. An inhabitant of deep waters near offshore islands and the drop-offs of continental shelves, this species is not as fully oceanic as the closely related Blue (Prionace glauca) and Oceanic Whitetip (Carcharhinus longimanus) Sharks. But Silkies are often encountered in prodigious numbers, attesting to their success in semi-oceanic waters.

Just the Facts:

Size:

Reproduction:

Diet:

Habitat: Rocky Reefs, Open Ocean, Deep Sea Depth: surface to at least 1,650 ft (500 m) Distribution: Central Pacific, Tropical Eastern Pacific, Chilean, Western North Atlantic, Caribbean, Amazonian, Argentinean, Eastern North Atlantic/Mediterranean, West African, Southern African, Madagascaran, Arabian, Indian, South East Asian, Western Australian, Southeast Australian/New Zealand, Northern Australian, Japanese |

In the tropics, Silky Sharks apparently do not have a set breeding period, giving birth year-round. But in the warm-temperate waters of the Gulf of Mexico, this species gives birth in summer from June through August. Six to fourteen pups are dropped in coastal waters over the continental shelves, but move seaward of the shelf drop-off by their first winter when they are 6 months of age. Their smallish size at birth — 27 to 30 inches (70 to 75 centimetres) long — renders Silky pups vulnerable to predation by large sharks. However, survival of very young Silky Sharks is probably enhanced by rapid growth. Neonate Silkies increase their length at birth by 10 to 12 inches (25 to 30 centimetres) by their first winter and reach a length of about 45 inches (115 centimetres) by the time they are one year old.

Juvenile and adolescent Silky Sharks often form loose aggregations, a strategy that probably helps to protect them from predators. Although they are quite sociable with members of their own species and often intermix with schooling Scalloped Hammerheads (Sphyrna lewini), Silkies in the tropical eastern Pacific tend to avoid Oceanic Whitetips when they can and defer to them on those occasions when their paths cross. Several species of jacks (family Carangidae) often travel with adult Silky Sharks, possibly using the sharks to get close to their prey (which are too puny for the sharks to bother with) or feeding on scraps from their hosts’ meals. Jacks also apparently use Silkies as convenient chafing posts — an activity that seems to annoy the sharks, causing them to twitch and accelerate each time they are hit.

Silky Sharks feed primarily on offshore fishes, but they also eat squids and pelagic crustaceans. Recently, a group of Silkies was filmed off Cocos Island, Costa Rica, feeding on a “bait ball” of sardines (probably the Pacific Sardine, Sardinops sagax). The sharks slashed open-mouthed through the pulsing, tightly wheeling mass of silvery fishes, catching them at their jaw corners and swallowing them whole. The sharks appeared to work the school of baitfish more-or-less independently, but were quick to take advantage of ‘star bursts’ of escaping sardines induced by one another. Mixed in among the swirling mêlée were several Striped Marlin (Tetrapterus audax), their silvery flanks ablaze with white-hot ‘feeder bars’, advertising their predatory excitement. The Silkies and Marlins seemed to ignore each other, feeding efficiently until — despite the best anti-predatory tactics of the sardines — every last baitfish was consumed. Afterward, the sardines’ violent death was punctuated by a constellation of silvery scales glinting in shafts of underwater sunlight as they slowly sank from sight.

Little is known about how Silky Sharks locate prey in the huge expanse of water off oceanic islands and continental landmasses. Experiments conducted in deep water off the Straits of Florida and in the “blue holes” at Tongue of the Ocean, Bahamas, have shown that Silkies are highly responsive to certain sounds. Attracted purely by sound, Silkies have quickly and repeatedly been drawn from one research vessel to another, separated by a distance of several hundred yards (metres). Their ability to home-in efficiently on irregular pulsed sounds may help Silky Sharks locate the frenzied feeding activities of seabirds, tunas, and/or dolphins. Such a splashing, pulsing, thrumming commotion is likely to indicate a predatory bonanza for hunting Silkies, sounding a dinner bell too tempting to pass up.

Experiments off Florida and the Bahamas have also demonstrated that Silky Sharks are most attracted to irregularly pulsed, low-frequency sounds of 10 to 20 Hertz (cycles per second). These sound characteristics correspond well to the rotor frequency of U.S. Coast Guard helicopters, as transmitted underwater. This coincidence suggests that using a helicopter to hover over downed survivors of an air-sea disaster may inadvertently draw potentially dangerous Silkies and other sharks to the area.

Silky Sharks are large, well-armed, inquisitive and potentially dangerous

to humans in the water. But they have far more cause to fear us than we have

to fear them. In tropical and warm temperate offshore waters world-wide,

Silkies are among the most common components of bycatch in the tuna fishing

industry. Trapped Silky Sharks often prey on tunas trapped in the same nets

as they, sometimes biting and entangling in the nets. In the tropical

eastern Pacific, their habit of damaging or destroying tuna nets has

earned

Silky Sharks the hated nick-name, “net-eater shark”. Perhaps in retaliation

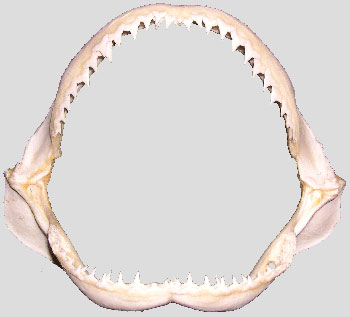

or out of sheer opportunism, many tuna fishermen remove the Silkies’ most

valuable fins for the Asian shark fin soup market and remove their jaws to

be sold as curios.

earned

Silky Sharks the hated nick-name, “net-eater shark”. Perhaps in retaliation

or out of sheer opportunism, many tuna fishermen remove the Silkies’ most

valuable fins for the Asian shark fin soup market and remove their jaws to

be sold as curios.

Thus, as a reflection of their abundance, Silky Sharks have the dubious distinction of being among the most abundantly represented species in Asian shark fin markets and are by far the most common source of cleaned and dried shark jaws sold to tourists in tropical countries.