Open Ocean: the Blue Desert

Blue Shark

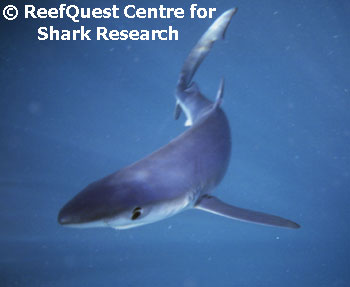

Lithe as a snake and graceful as any bird, the Blue Shark (Prionace glauca) is among the most beautiful of sea creatures. Its long snout pocked with large, white-rimmed eyes, elegant, scimitar-shaped pectoral fins, and flanks of brilliant ultramarine render this shark easily recognizable. But a cluster of subtler features make it ideally suited to the challenges of the open sea.

Just the Facts:

Size:

Reproduction:

Diet:

Habitat: Rocky Reefs, Kelp Forests, Open Ocean, Deep Sea, Polar Sea Depth: surface to 725 ft (220 m) Distribution: Arctic, Antarctic, North Pacific, Central Pacific, South Pacific, Temperate Eastern Pacific, Tropical Eastern Pacific, Chilean, North Atlantic, South Atlantic, Western North Atlantic, Caribbean, Amazonian, Argentinean, Eastern North Atlantic/Mediterranean, West African, Southern African, Central South Indian, Madagascaran, Arabian, Indian, South East Asian, Western Australian, Southeast Australian/New Zealand, Northern Australian, Japanese |

Consider the Blue Shark’s gills: on the inner margin of each gill bar are a series of finger-like gill rakers which prevent prey from escaping out the gill slits. This deceptively simple adaptation equips the Blue Shark to dine on even the smallest creatures, such as anchovies, pelagic salps, and even tiny, shrimp-like crustaceans known as “krill”. Blues have actually been filmed off southern California swimming open-mouthed through aggregated ‘balls’ of krill, straining them from the water in a manner reminiscent of feeding baleen whales. In the calorie-depauperate expanse of the open ocean, this ‘straining’ technique enables the Blue Shark to take advantage of food sources not available to other predatory sharks.

Nifty as is this trick, the Blue Shark catches most of its prey with its teeth. But its teeth, too, are well adapted to grant it dietary flexibility. The Blue Shark’s teeth are slender-tipped and serrated in both jaws, but the uppers have overlapping bases and are broader than the lowers. This arrangement enables it to grasp slippery-bodied prey that is small enough to swallow whole as well as to tackle larger food sources. Dietary studies have shown that a Blue Shark’s menu consists mostly of pelagic squids and schooling fishes. But, thanks to its dentition, the Blue is not restricted to such a limited diet.

Like other sharks, Blues will scavenge whenever the opportunity arises. A whale carcass, for example, represents a tremendous quantity of fat and protein to those scavengers who have the food processing equipment to take advantage of it. In such an event, a Blue Shark’s narrow lower teeth act as forks to hold on securely while vigorous head-shaking causes the broad, overlapping upper teeth to function as steak knives, efficiently sawing out bite-sized gobbets of flesh. Due to their slender build, however, Blue Sharks are sometimes competitively displaced from whale carcasses by larger species, such as the massive White Shark (Carcharodon carcharias). However, far out to sea in temperate waters, a whale carcass is likely to become the exclusive domain of Blue Sharks drawn from far and wide. But a whale carcass is a rare windfall and downright tiny compared to the enormity of the surrounding ocean.

Finding a meal in the vast emptiness of the open ocean is no easy task. Based on studies carried out on other sharks, Blues probably rely on hearing and scent tracking to detect large concentrations of potential prey. Since Blue Sharks feed predominantly at night, at closer range they may rely on their large, well-developed eyes to detect the faint bioluminescence stimulated by prey movement or from specialized light-producing organs of the prey itself. Experiments in the wild suggest that electroreception may also play a significant role in detecting prey at night. But even the best sensory systems are useless without some kind of search pattern.

Sonic telemetry studies have revealed that Blue Sharks employ several hunting strategies, each characterized by distinct short-term movement patterns. Off Santa Catalina Island, California, from March to early June, Blue Sharks move inshore at night and offshore during the day. Beginning around midnight, the sharks move into shallow waters off Santa Catalina and feed on small schooling fishes – principally Northern Anchovies (Engraulis mordax) – returning to offshore waters by dawn. In contrast, from June to October, Blue Sharks remain offshore day and night, where they feed heavily on pelagic squids. From December through February, Blue Sharks also move inshore at night to take advantage of incredibly rich feeding provided by the winter mass spawnings of Market Squid (Loligo opalescens). Thus, at least off Santa Catalina, circadian and seasonal movements of Blue Sharks are strongly correlated with movement patterns of their prey.

Telemetry studies conducted off New England, from Georges Bank to Cape Hatteras, have shown that Blue Sharks regularly move up and down in the water column. These vertical oscillations are most pronounced during daylight hours and smaller in amplitude at night, when they are confined to depths near the thermocline. Several theories have been advanced to explain the functional significance of this behavior, but most of them strike me as overly convoluted. Since similar vertical oscillations have been recorded in other large open ocean fishes – including tunas, billfishes, and sharks – I suspect that these movements may simply be an expedient way of searching a wide section of the water column.

Three lines of evidence support my theory. All of the fishes in which similar movement patterns have been recorded – including the Blue Shark – feature large, well-developed eyes. Underwater lighting can be tricky, characterized by flickering light and subdued contrasts of light and shade. Moving up-and-down through the water column may help visually scan for potential prey. A glint of underwater sunlight or shadow that remains fixed as the hunter shifts depth could betray the presence of potential prey. Further, since oceanic water masses tend to stratify by density, odors that may signal an injured or dead animal tend to be smeared horizontally between water layers of similar density. Thus, swimming continually through as many strata as possible maximizes a predator’s chances of detecting an attractive scent. Lastly, an entire community of fishes, squids, and other creatures rises from the mesopelagic zone at night and remains near the surface until shortly before dawn, when it retreats en masse to the twilight depths. This might explain why the vertical oscillations of Blue Sharks are more confined at night, since remaining above the thermocline would probably maximize encounters with potential prey from the mesopelagic. Thus, the up-and-down movements of Blue Sharks in the western North Atlantic may represent a simple but effective hunting strategy.

Impressive as are the Blue Shark’s hunting strategies, they pale in

comparison with its long-distance movements. Tagging studies in the North

Atlantic have revealed that Blues are the champion migrators among sharks.

Blue Shark migrations of 1,200 to 1,700 miles (2,000 to 3,000 kilometres)

are common. The record to date for a tagged Blue Shark is a journey of 3,740

miles (5,980 kilometres) from New York to Brazil. But that’s only part of

the story. Piecing together the details of the Blue Shark’s epic journeys in

the North Atlantic is a hard-won triumph of countless researchers working on

both sides of that ocean basin over a period of more than four decades. How

Blue Sharks undergo such long hauls and why is among the most astonishing

stories in marine biology.

Impressive as are the Blue Shark’s hunting strategies, they pale in

comparison with its long-distance movements. Tagging studies in the North

Atlantic have revealed that Blues are the champion migrators among sharks.

Blue Shark migrations of 1,200 to 1,700 miles (2,000 to 3,000 kilometres)

are common. The record to date for a tagged Blue Shark is a journey of 3,740

miles (5,980 kilometres) from New York to Brazil. But that’s only part of

the story. Piecing together the details of the Blue Shark’s epic journeys in

the North Atlantic is a hard-won triumph of countless researchers working on

both sides of that ocean basin over a period of more than four decades. How

Blue Sharks undergo such long hauls and why is among the most astonishing

stories in marine biology.

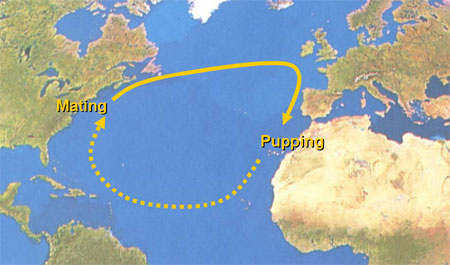

Our story begins in the western North Atlantic. Here, Blue Shark mating takes place during spring and early summer, principally from May through July. As in other sharks, Blue Shark courtship is a rather rough affair, with amorous males frequently biting females’ backs and flanks as a prelude to intromission. These ‘love nips’ do not harm the female Blues, as their skin is proportionately more than twice as thick as that of males — actually thicker than the males’ teeth are long. Examination of reproductive tracts of Blue Sharks off New England has revealed another very curious fact: many of the recently-mated female Blue Sharks in the western North Atlantic are not yet sexually mature.

Tagged Blue Sharks captured farther east in the North Atlantic provide additional clues about what’s going on here. It turns out that most male Blue Sharks tagged in the western North Atlantic remain there and the vast majority of transatlantic Blues are females. Further examination of their oviducts has revealed that, like certain other sharks, female Blues store sperm packets — each containing hundreds of thousands of helical spermatozoa — in special sacs in their reproductive tracts called “shell glands”. Further, it is now apparent that, as they migrate eastward across the North Atlantic, adolescent female Blues mature and begin passing ripe ova through their shell glands where the sperm packets are stored and fertilization takes place. Thus, some 10 to 20 months after a female Blue Shark was inseminated in the western North Atlantic, she self-fertilizes during her epic eastward migration.

To conserve energy on their long migration, female Blue Sharks apparently ride open ocean currents. Tagging results strongly suggest that female Blue Sharks from the western North Atlantic follow the course of the clockwise-flowing North Atlantic Gyre, journeying from west to east in the Gulf Stream and North Atlantic Current to reach pupping grounds off Spain, Portugal and the eastern Mediterranean. Blue Sharks give birth to very large litters — commonly 25 to 50 pups per litter, but as many as 135 pups have been reported from a particularly fecund mother Blue. Such large litters suggest that the open ocean is a hazardous place for the 16-inch (40-centimetre) pups.

As if all this were not remarkable enough, tagging results also show that at least some female Blues tagged in the western North Atlantic eventually return to those waters. Therefore, the next leg of the Blue Sharks’ journey could take them south in the Canaries Current, after which those returning to America find the North Equatorial Current and follow it back across the North Atlantic to the Caribbean. The last leg of their journey might see the female Blue Sharks heading north again in the Gulf Stream to return to traditional mating sites off the New England coast. The total trip, from New York to Europe to Africa to the West Indies and back to New York is about 9,500 miles (15,000 kilometres). At an average speed of 23 miles (37 kilometres) per day, the entire voyage might take about 14 months. But this would not leave a lot of time for pupping, feeding, or other vital activities in which female Blue Sharks engage while en route.

Alternatively, female Blues from the western North Atlantic could travel home via a shorter route. By keeping to the Atlantic side of the West Indies and the Bahamas on the way to Cape Hatteras, the sharks could ride the slow open ocean currents on the last leg of their epic journey, drifting back to New York at an average speed of 0.5 miles (0.8 kilometres) per hour. A shark following this route would probably take 25 months to complete the entire North Atlantic circuit.

If, as in many sharks, female Blues take a year off between giving birth and mating again, the entire reproductive cycle of this species may take as long as three years. Preliminary population genetics work suggests that the Blue Sharks of the western and eastern North Atlantic represent a single breeding stock. As such, the North Atlantic Blue Shark population is highly vulnerable to directed fishing pressure and wise management of this beautiful, efficient, and far-ranging species will require the active cooperation of the many nations surrounding this ocean basin.