Order Orectolobiformes:

Carpet Sharks — 39 species

- two, spineless dorsal fins

- a very short, transverse mouth that is well anterior to the eyes

- specialized nostrils, with prominent barbels and nasoral grooves connecting the nostrils to the mouth corners in most forms (wobbegongs, of the family Orectolobidae, have — in addition — complex dermal flaps around the margin of the head, which serve to obscure their outline while lying on the bottom)

- spiracles small to very large, located below the eye (except the whale shark in which they are located behind the eye)

- most with small gill slits, with the fourth overlapping the fifth (again, except for the whale shark, which has large, non-overlapping gill slits) and behind origin of the pectoral fin

- most species have a caudal fin with an upper lobe that is more-or-less in line with the main body axis (not tilted upward, as in most other sharks) and a poorly-developed lower lobe (except in the whale shark — the only fully pelagic orectoloboid — which has a large, well-developed lower caudal lobe); the order's scientific name translates roughly to "stretched-out lobe", in reference to the tail type characteristic of the group

- reproduction variable, either oviparous or ovoviviparous (depending on species)

- exclusively marine, most inhabiting shallow to moderately deep warm temperate to tropical zones of Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian oceans; the group is most richly represented in the tropical Indo-West Pacific region

- 13 genera in 8 families

|

|

|

A representative orectoloboid, the Nurse Shark (Ginglymostoma cirratum), showing the finger-like nasal barbels, short, transverse mouth completely in front of the eyes, overlapping fourth and fifth gill slits, dorsal fins far back on the body, and horizontal caudal fin with weakly developed lower lobe characteristic of the group. The teeth, like those of most carpet sharks, are multi-cusped, with a strong central cusp flanked by two or more secondary cusplets.

The orectolobiform sharks are a tremendously diverse group, making it difficult to do justice to their extraordinary variety.

The Tawny Nurse Shark (Nebrius ferrugineus)

inhabits coral reef areas of the tropical Indo-West Pacific. The

superficially similar Nurse Shark (Ginglymostoma cirratum) inhabits

shallow tropical waters of the eastern Pacific and both sides of the

Atlantic. Note that the mouth is located completely anterior to the eyes,

a characteristic shared by all orectoloboids.

The Tawny Nurse Shark (Nebrius ferrugineus)

inhabits coral reef areas of the tropical Indo-West Pacific. The

superficially similar Nurse Shark (Ginglymostoma cirratum) inhabits

shallow tropical waters of the eastern Pacific and both sides of the

Atlantic. Note that the mouth is located completely anterior to the eyes,

a characteristic shared by all orectoloboids.

Photo © David Fleetham david@davidfleetham.com; used with the gracious permission of the photographer.

In terms of size, the orectoloboids range from the small Barbelthroat Carpetshark (Cirrhoscyllium expolitum) — which is known from a single, mature specimen about a foot (30 centimetres) in length — to the enormous filter-feeding Whale Shark (Rhincodon typus) — the largest living fish, which grows to a length of at least 45 feet (14 metres). This group also includes the Nurse Shark (Ginglymostoma cirratum), which grows to a respectable length of 9 feet (2.8 metres) and is familiar to many sport divers and aquarium visitors.

Resembling an unmade bed with fins, the Tasseled Wobbegong (Eucrossorhinus dasypogon) avoids detection by masking its piscine nature. The outline of its head is obscured by a complex beard of dermal flaps and its entire body is elaborately camouflaged, broken into small, unrecognizable shapes by a network of dark markings on a pale background. This species grows to a length of 10 to 13 feet (3 to 4 metres) and inhabits coral reefs from the interidal down to a depth of at least 130 feet (40 metres) off Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, and northern Australia. The Tasseled 'Wobby' is often encountered by divers in this region, usually found resting in caves or under ledges during daylight hours, where it may feed on nocturnal fishes (such as squirrelfishes, soldierfishes, and sweepers) that share its cave. At night, individuals of this species are believed to leave their daytime resting places to hunt, clambering over the reef face on its highly mobile pectoral and pelvic fins, searching in nooks and crannies for sleeping diurnal fishes and nocturnal crustaceans.

The orectoloboids are also wonderfully varied in terms of form, lifestyle, color and pigmentation pattern. They range from the other-worldly Tasseled Wobbegong (Eucrossorhinus dasypogon) — which is an elaborately camouflaged ambush predator — to the elegant Zebra Shark (Stegostoma varium) — which has a tail longer than its body and exchanges its zebra-stripes for leopard-spots as it matures — and the delicately slender Epaulette Shark (Hemiscyllium ocellatum) — which actively hunts inside the cramped and convoluted passageways within coral reefs. The colllard carptsharks (family Parascylliidae), which may be found over muddy, sandy, or rocky bottoms can change color to match the seafloor type.

Named for the conspicuous large dark patch on the 'shoulder', the Epaulette Shark (Hemiscyllium ocellatum) uses its paddle-like, highly mobile pectoral and pelvic fins to clamber salamander-like over the substrate. It is one of the few fishes that, when startled or frightened, will try to 'walk' away rather than swim. Growing to a maximum length of only 42 inches (107 centimetres), this species feeds on small, bottom-dwelling critters — such as worms, shrimps, and crabs, which are snuffled out of the sand or sucked forcibly from coral crevices. The Epaulette Shark is restricted to shallow coral reef areas of northern Australia and New Guinea, where it ranges from the intertidal to a depth of about 30 feet (10 metres). It is most commonly encountered perambulating among staghorn corals on reef faces and flats, but is often found hunting in tidepools. Because of its small size and endearingly clumsy locomotion, the Epaulette Shark is pathetically easy for beachgoers to catch. Captured individuals squirm vigorously and, although they cannot inflict serious damage on their tormentors, they are often injured in the ordeal.

Many carpet sharks are beautifully patterned with spots, saddles, ocelli, or mottled markings, hence the group's common name. These patterns are important as camouflage, as many orectoloboids are nocturnal, spending the daylight hours lying motionless and undetected on the bottom. In Australia, wobbegongs have a particularly nasty reputation because, when stepped on by a careless wader, some of these cryptic, dagger-toothed sharks had the audacity to react defensively. Many bottom-dwelling forms — such as the wobbegongs (family Orectolobidae), collared carpetsharks (Parascylliidae), and the bamboosharks (Hemiscylliidae) — have rounded, highly mobile pectoral and pelvic fins, which they use to clamber over the bottom like elongated salamanders with ping-pong paddles for legs. In recent experiments by P.A. Pridmore, the bottom-walking behavior of the Epaulette Shark served as the model for the limb coordination that eventually enabled a tetrapod pioneer (probably an amphibian or proto-amphibian) to invade the terrestrial environment.

Reproduction in carpet sharks is variable. Some orectoloboids (such as the Epaulette and Zebra Sharks) are oviparous, while others (such as the Nurse Shark and wobbegongs) are ovoviviparous. Until very recently, it was widely assumed that the Whale Shark was oviparous, based on a single shoebox-sized egg case containing a 14.5-inch (37-centimetre) embryo, collected from the northern Gulf of Mexico in July 1955. But this egg case was thin-shelled and lacked anchoring tendrils, unlike the eggs of most oviparous sharks. In July 1995, a 35-foot (10.6-metre) long pregnant whale shark harpooned off eastern Taiwan was found to contain 301, 2-foot (60-centimetre) embryos — by far the largest litter recorded from any shark — proving, once and for all, that this species is ovoviviparous.

Growing to a length of at least 45 feet (14 metres), the Whale Shark (Rhincodon typus) is an enormous filter-feeder. Its filtering mechanism consists of stacked triangular plates of spongy tissue that bridge the gaps between successive gill bars. A versatile suction-feeder, the Whale Shark strains a wide variety of planktonic and nektonic creatures from the water. Masses of small crustaceans and other drifting organisms are regularly consumed, along with squids and small to not-so-small fishes such as sardines, anchovies, shark suckers (ingested accidentally?), mackerels, and even small tunas and albacores. This species is typically solitary, but may aggregate in patches of ocean where plankton is richly concentrated. The Whale Shark feeds at or near the surface, sometimes assuming a vertical orientation with its terminal mouth uppermost. Whale Sharks often enhance the efficiency of vertical feeding by 'bobbing' up and down in 15- to 20-second cycles, pausing at the surface to let food-bearing water rush into their mouths and strain through their gill plates The great pioneer shark biologist, Stewart Springer, once reported that he saw several tuna appear to leap into the mouth of a vertically-feeding Whale Shark at the completion of each 'bobbing' cycle. If Whale Sharks actually swallow the large fishes they suck in — accidentally or otherwise — they must add considerably to the sharks' protein intake.

In 1986, Guido Dingerkus revised the orectoloboids, recognizing only five families, but his scheme — although it raises many points worthy of consideration — has not been widely accepted and is not adopted here. I prefer to follow Compagno (1988) in regarding the collared carpet sharks (Parascylliidae) as the primitive sister taxon for the group, rather than the epaulette sharks (Hemiscylliidae) as proposed by Dingerkus. One recommendation Dingerkus made in his 1986 paper that I have adopted is placing the Short-tailed Nurse Shark in its own genus (Pseudoginglymostoma), distinct from that of the nurse shark (Ginglymostoma).

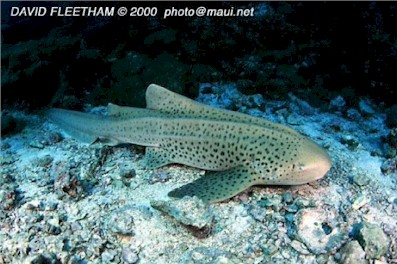

The beautiful Zebra Shark (Stegostoma

varium) is named for the vertical back-and-white bars it sports

as a juvenile. This species' shares longitudinal dermal ridges and

numerous internal characters with the Whale Shark (Rhincodon

typus), indicating a close evolutionary relationship between these

superficially very different sharks.

The beautiful Zebra Shark (Stegostoma

varium) is named for the vertical back-and-white bars it sports

as a juvenile. This species' shares longitudinal dermal ridges and

numerous internal characters with the Whale Shark (Rhincodon

typus), indicating a close evolutionary relationship between these

superficially very different sharks.

Photo © David Fleetham david@davidfleetham.com; used with the gracious permission of the photographer.