Sandy Plains: No Place to Hide

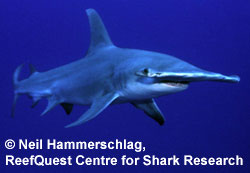

Great Hammerhead Shark

Unlike other hammerhead sharks, the Great Hammerhead (Sphyrna mokarran) is completely unafraid of humans. Fortunately for divers and swimmers, this species does not seem to be particularly interested in humans, either. Great Hammerheads often exude an air of complete confidence as they glide majestically past divers, apparently keenly aware of their own imposing size.

Just the Facts:

Size:

Reproduction:

Diet:

Habitat: Intertidal, Estuaries, Sandy Plains, Rocky Reefs, Kelp Forests, Coral Reefs, Open Ocean, Deep Sea, Polar Sea, Fresh Waters Depth: 3-260 ft (1-80m) Distribution: South Pacific, Tropical Eastern Pacific, Chilean, Western North Atlantic, Caribbean, Amazonian, Eastern North Atlantic/Mediterranean, West African, Madagascaran, Arabian, Indian, South East Asian, Western Australian, Southeast Australian/New Zealand, Northern Australian, Japanese |

Growing to a length of at least 18 feet (5.5 metres), the Great Hammerhead Shark is by far the largest hammerhead and among the very largest of sharks. Unfortunately, age and growth in this species have not been extensively studied and many inconsistencies occur in the literature on its life history. The Great Hammerhead’s sheer size may be a factor in our poor understanding of its basic biology, as most specimens are too large to transport or store.

Due, in part, to its large size and conspicuous appearance, the diet of the Great Hammerhead Shark is fairly well known. Feeding mostly at dawn and dusk, the Great Hammerhead preys on a wide variety of creatures — including other sharks, tarpon, sardines, sea catfishes, toadfishes, jacks, herrings, groupers, boxfishes, squids, and crabs. But of all its prey types, the Great Hammerhead has a particular gastronomic preference for rays, including guitarfishes, stingrays, cownose rays, eagle rays, and skates. Off southern Africa, 41% of Great Hammerhead stomach contents included guitarfishes and stingrays. According to one study conducted in western Africa, 86% of Great Hammerhead stomachs contained a single species of stingray, the Daisy Stingray (Dasyatis margarita). The Great Hammerhead does not seem to be bothered at all by the stingrays’ sharp, venomous defensive spines — one large individual caught off Florida had an incredible 96 stingray barbs embedded in its mouth, throat, and ‘tongue’! It was reported to be “a living dynamo” when captured.

Stingrays are superbly adapted to feeding and avoiding predators on subtidal sandy plains, and often occur in these habitats in astounding numbers. All stingrays have a short, transverse mouth armed with teeth flattened into crushing plates that are well-suited to crushing the hard shells of buried molluscs and crustaceans. The flattened bodies, raised eyes, and large spiracles (accessory respiratory organs) of these rays are specialized for lying motionless on soft sediments, drawing oxygen-bearing water from above their heads, passing it over the delicate gill membranes, then pumping it discretely out through the gill slits. Partially buried with sand, a resting stingray is able to draw particulate-free water over its gills while remaining virtually invisible.

But the Great Hammerhead Shark has a definite fondness for stingray flesh, and is well adapted to finding its cryptic prey. Most obvious among the Great Hammerhead’s prey-detecting mechanisms is the ‘hammer’ itself. Ridges on the crowns of the dermal denticles along the hammer’s leading edge are oriented to guide scent-bearing water along specialized grooves leading to the nares (nostrils), which are located near the tips of the laterally expanded head. Because its nares are separated by a distance of up to 3 feet (1 metre), the Great Hammerhead is able to chemically sample an unusually wide portion of the water column, enabling it to home in on attractive odors with uncanny precision. The hammer also serves as an efficient electrosensor by allowing the ampullae of Lorenzini to be spread over a wide area. The location of a buried stingray may thus be betrayed by the tiny, electrical pulse that keeps its heart and spiracles beating. By swimming close over sandy bottom and swinging its head through wide arcs, the Great Hammerhead uses its laterally expanded head like the sensor plate of a metal detector. This cephalic endowment probably grants the Great Hammerhead a significant competitive advantage over non-hammerheaded sharks in detecting buried stingrays.

Recent anatomical work suggests that hammerheads can finely control their hammers’ angle of attack. This ability may grant the Great Hammerhead added maneuverability that helps it to capture prey. On several occasions, I have seen solitary Great Hammerheads swimming close over the bottom, swinging their strange, T-shaped heads through an arc of perhaps 120 degrees. In each case, the shark suddenly curled its pectoral fins in a breaking position and doubled back within a third of its own length to scoop up a stingray hiding in the sand as several others exploded from the bottom, leaving great billowing clouds of sediment. I have no doubt that the Great Hammerhead is exceptionally maneuverable for a shark of its size and believe this ability plays an important role in its predatory success — especially when feeding on stingrays, which are startlingly agile swimmers.

In May 1988, a Great Hammerhead was observed using its hammer in a novel and unanticipated way. Off Bimini, Bahamas, a 10-foot (3-metre) Great Hammerhead used its hammer to ‘bat’ a free-swimming Southern Stingray (Dasyatis americana) across its back, sending the ray crashing into the bottom. The Hammerhead then used its laterally expanded head to pin the pectoral ‘wings’ of the stingray against the bottom, preventing it from swimming away. The shark pivoted atop the stingray and bit off a chunk of the ray’s pectoral fin. When the Great Hammerhead circled for another bite, the Stingray resumed its escape attempt. Again the Hammerhead used its head to restrain the Stingray. The shark ripped another chunk from the ray and, after a longish break (perhaps inhibited by the presence of the observers), the Hammerhead grasped the moribund ray in its mouth and swam away.

The feeding strategy of this particular Great Hammerhead seems remarkably efficient and economical. If this behavior is typical, it may explain why Great Hammerheads are particularly adept at catching stingrays. In any case, it is clear that this species has a particular gastronomic predilection for stingray flesh. Since stingrays often spend their daylight hours resting on the vast, sandy plains of shallow bays, it is not surprising that Great Hammerheads often haunt these areas in search of their favorite prey.

Great Hammerhead Shark Bibliography

More about:

Origin and Evolution of the Hammer |

Hammerhead Taxonomy