Helicoprion: an Intriguing Puzzle

A cast of the holotype of

Helicoprion, first described in 1899 and discovered in the |

They came from mid-Permian deposits in Russia, North America, Japan, and Australia. Curious spiral structures, some 10 inches (26 centimetres) across - or about the size of a large dinner plate. At first, they were thought to be the coiled shell of a somewhat odd ammonite (primitive cephalopods with a spiraling external shell). On closer inspection, it was discovered that they were a continuous whorl of teeth or perhaps dermal denticles from some kind of shark. In short order, the creature was named Helicoprion and the game of trying to figure out how this structure might have fit onto a shark began in earnest. A Russian paleontologist named Andrzej P. Karpinski invested years of his life in futile attempts to restore the position of the whorl. Karpinski tried just about everything. He perched the whorl on top of the first dorsal fin, like some kind of bizarre windmill. He tried hanging it from the tip of the tail, coiled like a piglet's tail. He even placed the whorl on the tip of its nose, making the fish resemble a sinister swimming elephant.

|

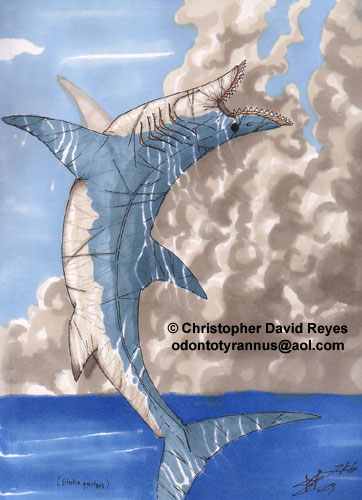

Reconstruction of Helicoprion by paleo-artist Christopher David Reyes (odontotyrannus@ aol.com). Christopher based his reconstruction on the fossil goblin shark, Scapanorhynchus. He is a freelance artist based in Brooklyn, NY, who creates reconstructions of extinct creatures as a hobby. |

It is now generally agreed that the structure is indeed a complex whorl composed of up to 180 teeth and must therefore have fit somehow into the mouth. Further specimens revealed that the teeth of Helicoprion most closely resembled those of a group of Paleozoic sharks known as edestoids. One of the best-known species, Edestus giganteus, was a 20-foot (6-metre) super-predator (about the same size of the modern white shark) with teeth that kept growing beyond the tip of its snout - looking for all the world like a fish with toothy pinking shears mounted on its nose. The most likely orientation - based on the teeth of Edestus and related edestoid sharks - is that the teeth overhang from the lower jaw like the vertical blade of a circular saw, having coiled about themselves as new teeth were generated from behind. Perhaps Helicoprion used this buzz-saw arrangement to snag squid-like creatures with a sideways swipe of the head while swimming through a school of the soft-bodied molluscs. In any case, Helicoprion exemplifies some of the difficulties involved in reconstructing ancient creatures from only a few clues.

The spectacular Scissor-Tooth Shark (Edestus giganteus), of the late Carboniferous, sported some of the weirdest dentition ever evolved. Like modern sharks, Edestus continually grew replacement teeth inside the jaws, but unlike them retained old, worn teeth until they protruded far in front of the fish’s head (thus the youngest teeth are at the rear of the jaws, while the oldest are at the tips). It is not known how Edestus actually used its pinking-shear jaws, but — as it grew to about the same length as the modern White Shark — it must have been a formidable predator indeed.

Painting by paleo-artist

Christopher David Reyes (odontotyrannus@aol.com).

Christopher is a

freelance artist based in Brooklyn, NY,

who creates

reconstructions of extinct creatures as a hobby.