Biology of the Sandtiger Shark

(Carcharias taurus)

| Field Marks | Both first and second dorsal fins and anal fin about equal in size; first dorsal fin origin closer to pelvic fin bases than pectoral bases; snout flattened, relatively short (less than mouth width); teeth slender, fang-like usually with single lateral cusplet on each side of main blade; 3 large anterior teeth on each side of upper jaw, separated from lateral teeth by a small intermediate tooth. Color light brown above, often with darker reddish or brownish spots scattered on flanks. |

| Size | Pups at birth about 37-41 in (95-105 m) long and 13 lb (6 kg) in weight; most individuals encountered by divers and anglers are 4-9 ft (1.8-3.7 m) long; maximum size is about 10.4 ft (3.2 m) and 640 lb (290 kg). |

| Range | Widely distributed in coastal areas of temperate and tropical seas. At this writing, reliably encountered year-round by scuba divers at: Seal Rocks, NSW, Australia; Aliwal Shoal, Natal Coast, South Africa; and the wreck of the tanker Papoose, off Cape Lookout, North Carolina; formerly abundant at another NC wreck, the US Navy submersible Tarpon, but after discovery of the wreck became common knowledge were all-but fished out at this location within a decade. |

| Habitat | Ranges from surf zone, in shallow bays, and around coral and rocky reefs to a depth of at least 625 ft (190 m), but usually found at a depth of less than 230 ft (70 m); sometimes enters mouths of streams. Often found near or on the bottom, but also occurs in midwater or near the surface. A strong but slow swimmer, more active at night; capable of hovering motionless in the water column, achieving near-neutral buoyancy by gulping air at the surface and holding it in the stomach. |

| Feeding | Preys on a wide variety of bony fishes, including herrings, croakers, bluefishes, butterfishes, snappers, hakes, eels, wrasses, mullets, spadefishes, sea robins, sea basses, porgies, remoras, sea catfishes, flatfishes, jacks, and undoubtedly many others; despite its deceptive sluggishness, capable of catching and consuming fast-swimming fishes such as bonitos and small tunas; elasmobranch prey includes carcharhinid and triakid sharks and myliobatoid rays; also known to consume squids, crabs and lobsters. Groups observed to feed cooperatively in some locations (off northeastern US and NSW, Australia), systematically surrounding and concentrating schooling prey before feeding; tail whip-cracking behavior may be used to frighten schooling fishes into compact groups. Studies of captive specimens indicate that rate of food consumption is low (about 2% of body weight/wk) and fluctuates seasonally, rations decreasing roughly 25% during winter months. |

| Reproduction | Ovoviviparous, 2 pups born per litter due to intrauterine cannibalism; gestation period 9-12 months, pups born head-first; off Florida pups are born November to February, off South Africa pups are born in Cape Waters from October to November, off New South Wales, Australia, pups may be born October to December (based on incidence of apparent neonates in mesh nets); individuals apparently bear young in alternate years, accumulating energy reserves for a year before mating again. Courtship features the male ritualistically biting the female's pectoral fin before mating and holding on with mouth while inserting one of his claspers into her vent; in western North Atlantic, certain North Carolina shipwrecks may be important mating grounds, while Virginia waters may be important pupping grounds. |

| Age & Growth | In western North Atlantic, males and females grow at similar rates, although females attain much larger size; growth for ages 0 to 1 is 10 - 12 in/yr (25 - 30 cm/yr), declining by approximately 1 in (2.5 cm) every yr to a minimum of 2-4 in/yr (5-10 cm/yr); males reach maturity at 6.2-6.4 ft (1.9-1.95 m) in length at an age of 4 - 5 yrs; females reach maturity at a length of more than 7.2 ft (2.2 m) at an age of at least 6 yrs. Calculated maximum length for males is 9.9 ft (3 m), for females 10.6 ft (3.2 m). Longevity in the wild at least 15 yrs. |

| Danger to Humans | Probably dangerous only if provoked; attacks usually result in little injury and are probably the result of defensive threat or accidental provocation; the International Shark Attack file lists 53 attacks attributed to this species, but many may be misidentifications. If persistently approached by divers, may give an agonistic display featuring jaw protrusion, resembling an exaggerated 'yawn' or 'gape'; at Protea Banks, South Africa, females in caves have directed tail whip-cracking at divers, possibly signaling defensive threat. Adult males are reported to be more aggressive during their mating season. |

| Utilization | Fished virtually everywhere it occurs, but of varying importance regionally; highly regarded as food in Japan, but not in America. Caught primarily with line gear, but also taken on fixed bottom gillnets, in pelagic and bottom trawls. Meat is utilized fresh, frozen, smoked, dried and salted; also used for fishmeal, its liver for oil, and its fins for the Oriental sharkfin trade. Not considered a game fish, as it generally offers only sluggish resistance to being caught on hook and line; IGFA all-tackle record is 350 lb 2 oz (158.81 kg), caught off the municipal jetty at Charleston, South Carolina, in April 1993. A hardy species that adapts well to captivity, record longevity in captivity is 16.6+ yrs. |

| Remarks | Victimized largely due to its deceptively ferocious appearance; in

Australia, this once-common shark was decimated by 'sport divers' armed

with powerheads; Australia declared it federally protected in 1997;

populations in some areas are slowly beginning to recover, but the species

is still not nearly as abundant as it once was. Listed as 'vulnerable' (VU

A1ab+2d) in IUCN Red Data List, declared a protected species in the

western North Atlantic by US National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS 50

CFR, Pt. 678), April 1997. Update: the status of the Sandtiger Shark in Australia (where it is known as the Grey Nurse Shark) has been reclassified. There are now only about 500 individuals left on the east coast, they are listed as endangered or critically endangered depending on whether you're looking at State or Federal legislation. The NSF Fisheries department has recently released a draft recovery plan for the species, which is available at: http://www.fisheries.nsw.gov.au/threatened_species/general/ species/Grey_Nurse_Shark In August 2006, the New South Wales Department of Primary Industries announced that it had committed AU$600 thousand to a Grey Nurse Shark breeding program, which relies on an artificial shark uterus their researchers developed and tested on non-threatened shark species. You can read more about this astonishing development in shark conservation at: http://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/archive/news-releases/fishing-and-aquaculture/2006/save-grey-nurse-shark |

Although most of us 'know better' than to make character judgments based on appearances, sometimes we just can't help ourselves. The Sandtiger looks more like a shark is supposed to look than most species actually do. With its cold, cat-like eyes and long, pointed snout overhanging a mouthful crammed with some of the wickedest-looking teeth in all of sharkdom, the Sandtiger seems to ooze malevolence from every ampullary pore. But in this case — as in so many others - appearances are misleading. Unmolested, the Sandtiger is a paper tiger of a shark, gentle and accommodating despite its ferocious appearance.

Due to its large size (up to about 10 feet or 3 metres in length), fierce countenance, and ability to adapt to captivity, the Sandtiger is a popular exhibit at public aquaria. For many people, the toothy Sandtiger has thus become their only personal encounter with sharks, representing the group and shaping their ideas about sharks as a whole. In fact, aquarium exhibit designers were largely responsible for "sandtiger shark" becoming the preferred vernacular name for this animal, as it sounded much more dramatic than the plainer, less-evocative "sand shark" that was previously in general usage. In Australia, the species is known as the Grey Nurse Shark; in South Africa, it is known as the Spotted Ragged-Tooth or "Raggie". But a shark by any other name would be as sweet natured. Only our reactions to this creature change depending on our preconceived ideas, as reflected in the names we bestow upon it. Popular conceptions about this animal are thus misled by both the aquarist's name and by the nature of life within an aquarium. A shark under glass cannot be expected to behave as it does in the wild, any more than you or I would behave 'normally' if confined to a bathroom for 10 or 15 years.

Despite these inherent problems, many interesting discoveries have been made about Sandtigers from the study of captive individuals. One of the most fascinating of these discoveries concerns their ability to regulate their buoyancy. Like other sharks, Sandtigers are more dense than water and tend to sink if they stop swimming. But Sandtigers, it turns out, are able to achieve near-neutral buoyancy by gulping air at the surface and holding it in the forward part of the stomach. This air gulping behavior has actually been seen in aquarium specimens, and only later (when divers knew what to look for) was it verified that Sandtigers do the same thing in the wild. There are even reports that captive Sandtigers sometimes expel gas from the cloaca, and it has been suggested that they may be able to fine-tune their buoyancy in this manner. This seems rather dubious. But perhaps the notion that sharks, like humans, pass gas on occasion can help foster a sense that they are really not all that different from us.

One fundamental way in which most (but not all) sharks differ from us is in their mode of embryonic nutrition. Sharks vary enormously in their reproductive patterns, but most species — including the Sandtiger and all other lamnoids - are at late stages of development nourished by a steady supply of tiny, unfertilized eggs. But the Sandtiger has taken this womb service to a goulish new level. About half-way through their 9- to 12-month gestation period — after the initial yolk supply had run out but before the supply of unfertilized eggs has begun — Sandtiger embryos develop precocious teeth and swimming ability. These features enable the Sandtiger embryos to make their own dining arrangements. The largest or strongest embryo in each uterus actually turns on its lesser siblings, vigorously attacking and consuming them. At this stage of development, the cannibalistic Sandtiger embryos are bubblegum pink in color, have grotesque, over-sized heads and eyes, and are only about 4 inches (10 centimetres) in length. This is the only known case of intrauterine (within the uterus) cannibalism in the Animal Kingdom, and it has been called "the ultimate solution to sibling rivalry". In the end, only two pups are born - one from each uterus. The advantage of this nightmarish strategy is the production of relatively large young — a 7-foot (2.2-metre) mother giving birth to a pair of three-foot (1-metre) pups. Such pups are big enough to discourage most would-be predators and are already experienced predators themselves.

Despite the popular conception of sharks as 'lone killers', many species feed in groups and a few even appear to co-operate in prey-capture. Sandtigers have occasionally been reported to feed co-operatively. In 1915, pioneer shark-watcher Russell J. Coles reported on the astonishingly co-ordinated manner in which a group of Sandtigers off Cape Lookout, North Carolina, concentrated and captured a school of Bluefish (Pomatomus saltatrix). According to Coles, a school of a hundred or more Sandtigers systematically surrounded the school of Bluefish and herded them into shallow water, where — at the same instant — the pack of sharks dashed in and attacked their nearly-stranded prey. Similar co-operative herding behavior and use of bottom topography to strand schooling fishes has often been observed in Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) feeding on mullet (family Mugilidae) at several coastal wetland locations off the southeastern United States. All schooling or herding animals crowd together instinctively when faced with a hunting predator. But, unless contained very skillfully, such prey animals tend to be quite adept at finding and flowing through any momentary opening and thereby making good their escape. Yet fishes - however exquisitely agile in their liquid element — are all-but helpless when confined in very shallow water. Thus, if Cole's report is reliable, it suggests that the Sandtigers employed basic understanding of the escape responses and limitations of their prey.

Such reports of co-operative feeding in Sandtigers are not uncommon. At Seal Rocks, New South Wales (about 185 miles or 300 kilometres north of Sydney, Australia), a diver reported a pack of Sandtigers — known locally as Grey Nurse Sharks — herding a small shoal of juvenile Yellowtail Kingfish (Seriola lalandi). The sharks accomplished this by whipping their tails to generate sharp underwater pressure waves, which sound very like the reports of a shotgun. This caudal fin whip-cracking immediately calls to mind the similar prey-stunning technique employed by thresher sharks (family Alopiidae) in open water when feeding upon small shoaling fishes. What is perhaps most intriguing, however, is that adult female Sandtigers in underwater caves at Protea Banks (off the Natal Coast of South Africa, near Durban), are known to perform a similar tail whip-cracking behavior toward divers, possibly indicating defensive threat. Similar tail whip-cracking behavior has been reported between two large White Sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) off the Cape Coast of South Africa. Thus, shark behaviors used in herding and disabling prey may also be employed ritualistically in agonistic encounters, whether directed toward members of their own species or monkeys encased in neoprene.

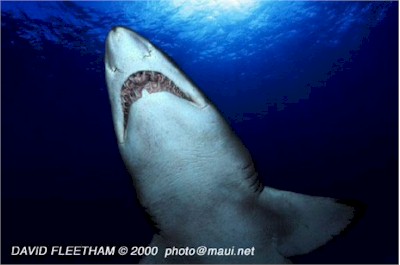

Also called Grey Nurse and Spotted Ragged-Tooth,

the Sandtiger (Carcharias taurus) is certainly one of the most ferocious-looking

of sharks. This species' prominent anterior teeth, bristling from its

mouth, make it seem far more dangerous to humans than it really is. Unless

cornered or molested, the Sandtiger is a gentle and accommodating creature that

can be observed by well-behaved divers at very close range. Which goes to

show that one shouldn't judge a shark by its appearance.

Also called Grey Nurse and Spotted Ragged-Tooth,

the Sandtiger (Carcharias taurus) is certainly one of the most ferocious-looking

of sharks. This species' prominent anterior teeth, bristling from its

mouth, make it seem far more dangerous to humans than it really is. Unless

cornered or molested, the Sandtiger is a gentle and accommodating creature that

can be observed by well-behaved divers at very close range. Which goes to

show that one shouldn't judge a shark by its appearance.

Photo © David Fleetham david@davidfleetham.com; used with the gracious permission of the photographer.

But sharks are generally remarkably unaggressive, only rarely behaving in a threatening manner. The Sandtiger, for example — if left in peace — is typically quite docile and often highly social. Large gatherings of Grey Nurse Sharks were once common in so-called "shark gutters" off the coast of southeastern Australia. During daylight hours, scores of these sharks would often gather in specific, traditionally used gutters, resembling nothing so much as a submerged herd of (rather toothy) cattle. The purpose of these Grey Nurse gatherings — if there is one — remains unknown: the sharks were uniformly peaceful and not obviously engaged in feeding or mating activity. It was as though these deceptively fierce-looking sharks were aggregating for the sheer pleasure of one another's company.

But in the early 1950's, disaster struck. A new, cruelly efficient weapon was devised to protect divers from supposedly abundant 'man-eating' sharks: the powerhead. A powerhead is essentially an underwater gun, consisting of a metal tube that contains in its tip a shotgun or high-powered rifle shell. This shell is held away from the firing pin by a spring. When the tip of the powerhead is pressed against an object, the firing pin is brought into contact with the shell and it discharges. The full force of the resultant explosion is thus directed into whatever the tip of the weapon is pressed against (inanimate object, fish, or human), causing massive and often horrific damage. Smaller creatures are literally blown to fish fluff, while larger ones — such as sharks — if not killed outright may struggle for many minutes, despite having massive parts of the head or body mushroomed outward or simply blown off. In the hands on an inexperienced or overly-excited diver, a powerhead could easily injure or kill the user or his buddy. This nasty and dangerous weapon was sometimes known by the euphemistic name, "smoky poky".

Using skin or scuba gear and brandishing powerheads, a veritable army of self-professed Australian "sportsmen" descended upon the unsuspecting flotillas of Grey Nurse Sharks, killing them by the hundreds. Because the Grey Nurse fit perfectly the popular conception of what a dangerous shark looks like, these divers were widely regarded as death-defying heroes, ever-willing to spin thrilling yarns of their desperate battles with fierce 'man-eating' sharks . . . at least as long as the beer flowed freely. In truth, these undersea 'battles' were extremely one-sided, requiring only that a powerhead-equipped diver swim up to the peacefully floating herd of Grey Nurses and blow the brains out of several of the unsuspecting sharks as easily — and with about as much personal risk — as a groundskeeper spearing rubbish in a municipal park. Even for divers who knew that the placid Grey Nurse was easy to approach and kill, the opportunity to appear a hero proved irresistible. Within a decade or so, the Grey Nurse Shark was rare in many areas where it had once been abundant, swept from the sea by human ignorance and bravado.

Appalled by the decimation of the peaceful Grey Nurse Sharks off New South Wales, Victoria, and South Australia, famed Australian underwater photographer and conservationist Valerie Taylor crusaded to have them governmentally protected. Thanks largely to Taylor's tireless efforts, in 1984 the Grey Nurse was declared a protected species in New South Wales. In 1997 this state protection became extended throughout Australia. Although they remain far less abundant than recorded historically, the Grey Nurse is slowly making a comeback in New South Wales, Victoria, South Australian, and Tasmanian waters. But perhaps most importantly, the Grey Nurse (a.k.a. the Sandtiger or Raggie) became the first species of shark to be afforded federal protection. This set an important precedent for elasmobranchs in particular, and now several species of shark — including the Great White — are afforded some degree of governmental protection.

Given the long and often bloody relationship between humans and sharks, this is an encouraging sign. Let's hope the trend continues. After all, our experience of the ocean — whether directly via skin or scuba diving or indirectly through the glass or acrylic window of an aquarium tank — would be very much diminished if we could no longer look upon the toothy countenance of the Sandtiger and its kin. In a time when Africa is no longer a Dark Continent and virtually every corner of the globe has been mapped, it inspires wonder and awe and fires or imaginations to know that there are 'monsters' out there still.