Rocky Reefs: Rich Feeding in Cool Waters

Bluntnose Sixgill Shark

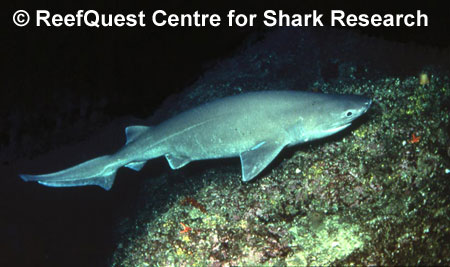

It has long been thought that the Bluntnose Sixgill Shark (Hexanchus griseus) is exclusively an inhabitant of the deep-sea. Due to its inaccessible habitat, virtually everything we knew about this species came from examination of lifeless specimens hauled up from profound depths. But off British Columbia, Canada, lives a population of Bluntnose Sixgills that seasonally enters uncharacteristically shallow waters, affording unique opportunities to observe, study, and swim with a visitor from a hostile realm we cannot readily visit.

Just the Facts:

Size:

Reproduction:

Diet:

Habitat: Intertidal, Rocky Reefs, Coral Reef, Deep Sea Depth: 10-8,200 ft (3-2,500 m) Distribution: Arctic, Central Pacific, Temperate Eastern Pacific, Tropical Eastern Pacific, Chilean, South Atlantic, Argentinean, Amazonian, Caribbean, Western North Atlantic, Eastern North Atlantic / Mediterranean, West African, Southern African, Madagascaran, Indian? South East Asian, Southeast Australian/New Zealand, Japanese |

I first learned of the shallow-water Bluntnose Sixgills when I moved to Vancouver, British Columbia, in 1990. Divers here had been aware it was possible to encounter these animals at certain locations off the British Columbian coast for thirty years, but none seemed to have any inkling of just how astounding and unprecedented is the phenomenon. Bluntnose Sixgills are among the most widely distributed of sharks, being found virtually worldwide. In temperate latitudes (but apparently not in the tropics), this species is a vertical migrator, ascending to shallower water at night and returning to the depths before dawn. But they typically haunt depths of 300 feet (90 metres) to at least 6 150 feet (1 875 metres) — far too deep for observation using conventional scuba gear, and much too expensive to study using deep-sea submersibles. Sporadically, a Bluntnose Sixgill turns up in relatively shallow water, but usually at night and never predictably. Yet here — virtually at my new doorstep — each fall, Bluntnose Sixgills could be reliably encountered at depths readily accessible by scuba — 60 to 90 feet (18 to 27 metres) during the day and as shallow as 10 feet (3 metres) at night. Recognizing the incredible research opportunity these sharks presented, I set about studying them at once.

Bluntnose sixgill with diver

At about the same time I learned of these shallow-water Sixgills, Provincial Fisheries did, too. To them, however, this unique population of deep-sea sharks in shallow water merely represented an underutilized protein source that could take some pressure off stocks of more traditional food fish depleted by unrelenting commercial fishing pressure. As an experiment, Bluntnose Sixgill meat was test marketed under the euphemistic name, “Snow Shark” and deemed quite acceptable. Extensive test fisheries were conducted in Barkley Sound, off the west coast of Vancouver Island. With my help and on their own, several local dive and marine conservation groups lobbied vigorously and tirelessly to have the fishery stopped and the Sixgills declared a protected species. Eventually the test fishery for shallow-water Bluntnose Sixgills was suspended, not due to the conservationists’ efforts, but on the grounds that catches were poor and falling off rapidly. But it was already too late for the Vancouver Island population. Sightings of Sixgills in Barkley Sound, formerly one of the best and most reliable sites for encounters with these sharks, had become few and unpredictable. Fortunately, a smaller inshore site off Hornby Island was not ‘hit’ by the test fishery and that population of shallow-water Sixgills escaped virtually unscathed, allowing my research to continue.

Shallow-water Sixgills are so remarkable because they are strongly adapted to the very different conditions of the deep-sea environment. For example, in the deep-sea, ambient light levels are very dim to nonexistent. As an adaptation to this darkness, the pupils of the Bluntnose Sixgill are permanently dilated — the muscles that formerly contracted the irises have atrophied from eons of disuse. In addition, the migratory pigment cells (which, in shallow-water sharks, migrate over the reflective plates behind the retina to prevent re-use of light under bright conditions) have been lost — so that the silvery plates are now permanently exposed, maximizing visual sensitivity to what little light wells down from the surface, far above. Small wonder that Bluntnose Sixgills are greatly distressed by even moderately high light levels: attempts to maintain specimens in captivity typically end when the brightness-blinded sharks knock themselves senseless through repeated collisions with tank walls.

A Bluntnose Sixgill swimming over a rocky reef face

Herein lies a clue to how Bluntnose Sixgills can enter shallow water off British Columbia each fall. British Columbian waters are very nutrient rich, and each fall plankton blooms reduce underwater light levels substantially. At depths of 70 feet or more, ambient light levels are very dim even at mid-day. I suspect that the reduced light levels caused by fall plankton blooms off British Columbia allow the normally deep-sea Bluntnose Sixgill Sharks to migrate up the steep continental slopes and enter uncharacteristically shallow water. In early winter, when plankton blooms die off and the water clears, the shallow-water Sixgills disappear — probably seeking refuge in deeper waters just offshore of their shallow-water sites. But why do these normally deep-sea sharks enter shallow waters in the first place?

Based on my on-going research, I suspect that Bluntnose Sixgills seasonally enter shallow waters off the coast of British Columbia — under cover of plankton blooms — to take advantage of the rich feeding available here. Arrival of these sharks in shallow water generally occurs from July or August, which coincides neatly with the local runs of Pacific Herring (Clupea pallasi). It seems that shallow-water Bluntnose Sixgills feed heavily on the larger fishes that aggregate each fall to prey on herring. From examination of stomach contents, I found that most British Columbian Sixgill prey consists of Spiny Dogfish (Squalus acanthias), Ratfish (Hydrolagus colliei), Pacific Hagfish (Eptatretus stouti), Cabezon (Scorpaenichthys marmoratus), and Lingcod (Ophiodon elongatus).

Underwater predation events are typically very sudden and of short duration, so they are rarely seen. However, I got lucky once and saw a shallow-water Bluntnose Sixgill catch and eat a Lingcod. The shark came up from deeper water, stalking its prey along a rock face. It then accelerated upward, turned, and come down vertically on the Lingcod, pinning the fish to the bottom with its snout. The Sixgill then pivoted, enabling it to swallow the Lingcod prey headfirst. The entire feeding event lasted only a few seconds, but is impressively methodical and efficient.

|

|

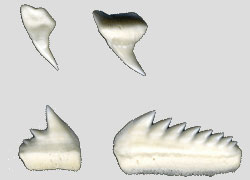

The upper teeth of Bluntnose Sixgills are numerous and thorn-like, while the lower are few — numbering about six on each side of the jaw — enlarged and multi-cusped, making each tooth resemble a cock’s comb. Such teeth are well suited to both grasping bite-sized prey and sawing hunks from food items too large to be swallowed whole. Dietary studies of Bluntnose Sixgills off California and South Africa indicate that this species feeds on just about anything it can clamp its jaws on. Off California, known food items include Prickly Sharks (Echinorhinus cookei), Pacific Lamprey (Lampetra tridentata), Hake (Merluccius productus) and other teleosts, whale blubber and pinniped remains. Off South Africa, Bluntnose Sixgills feed heavily on squids, other sharks, teleosts, and the largest individuals also feed upon Cape Fur Seals (Arctocephalus pusillus) and oceanic dolphins (family Delphinidae). Although Bluntnose Sixgills are clearly capable predators, it seems likely that the reported marine mammal food items were scavenged at the bottom.

In my studies, I have found evidence that Bluntnose Sixgills breed in shallow waters off British Columbia. Most of the Sixgills encounters at my Hornby Island research site are between 8 and 12 feet (2.4 and 3.6 metres) long, including sexually mature males and adolescent females. Some of the mature males have abraded clasper tips, swollen pink with the friction of piscine passion, and many of the adolescent females have scars on their backs near the dorsal fin (unlike most sharks, Bluntnose Sixgills have only a single dorsal fin) that are consistent with mating scars seen in other sharks. I have also caught newborn Bluntnose Sixgills — identifiable by a vitelline scar on the chest between the pectoral fins — in shallow waters just shoreward of sites where the mature males and adolescent females congregate.

Mother Bluntnose Sixgills typically bear large litters, which suggests a high juvenile mortality rate. When they are born, Sixgill pups are quite slender and have a caudal fin with a low thrust angle. They therefore swim with a very inefficient eel-like wriggle, which would make them highly vulnerable to predators such as Stellar Sea Lions (Eumetopias jubatus) and Killer Whales (Orcinus orca). I suspect that mother Bluntnose Sixgills in British Columbia waters drop their pups close inshore where there is plenty of food — including runs of Pacific Herring — for the pups to feed upon but few large predators to prey on them in turn.

Bluntnose Sixgill, showing large gill slits.

The offshore shallow-water sites also seem to offer the Bluntnose Sixgills of British Columbia opportunities for social interaction. According to preliminary results from my on-going studies, many of the same individual Sixgills return to favored sites year-after-year. There is very little observed agonistic (threat) display among the sharks, suggesting that social hierarchies are well established and highly stable. However, if pursued too aggressively or crowded by divers, shallow-water Sixgills often indicate their discomfort by holding their pectoral fins stiffly downward. If a diver persists or touches a Sixgill, it will often snap aggressively then dash away.

A small-scale but quite lucrative dive eco-tourism industry has developed due to the shallow-water Sixgills of British Columbia. Divers travel from as far away as Japan and Germany for an opportunity to swim eye-to-eye with shallow-water Sixgills. Collectively, these dive tourists inject some $10 million into the local economy.

It is presently illegal to retain a Bluntnose Sixgill caught in British Columbia waters, virtually eliminating the market for Snow Shark steaks. Lobbying to afford Bluntnose Sixgills full protection in British Columbia waters continues, including efforts to have the special places where they enter shallow waters declared marine parks. In this time of heightened ecological awareness, it makes far more sense to manage these shallow-water Sixgills as a living resource than to sell their carcasses for pennies a pound.

Bluntnose Sixgill Shark Bibliography

More on: Biology of the Sixgill |

Sixgill Research off western Canada